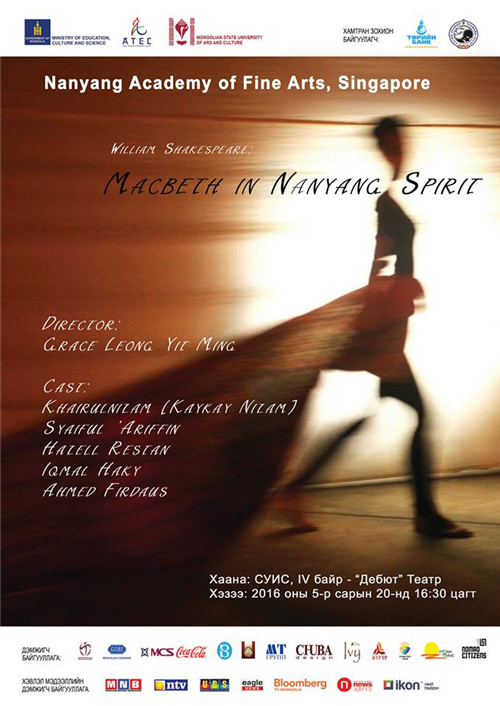

Director: Grace Leong Yit Ming

Playwright: William Shakespeare

Institution: Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts, Singapore

Venue: Debut theatre of SBMA, Mongolia

Time: 16:30, May 20, 2016

Event: 4th Asian Theatre Schools Festival

Director’s Notes

As a performing artist, I am dealing with a live art form that emerge in the moment of time, something elusively vital that lives in the body of a human being. It is like breathing oxygen into our body, we can't hold it in and leave it out for long, it needs constant exchange to make us alive and sustain our life. Yet what is air besides the scientific description of molecules? I am looking at a 'spirit' that personified in a form that is fluid, organic, and 'life' sustaining. The practice of Physical Theatre is a living live arts, it could generates momentous evidence that enhance the performers' presence, and hence actor always appear bigger on stage then in person. The practice of physical theatre also allow me to ascertain what makes physical form 'being' physical, it opens up new possibility for me to understand the relationship of ontological and epistemological in a human body, is like the air makes us alive in the body but the spirit give life to the being. Shakespeare's text always embodied an ' atmosphere' that describe beyond the physical form, it allows space for incubating imagination. As the actor layered movement onto the text or versa versus, it almost feels like they are breathing life to the dry bones and giving a new context for the audience. In the rehearsal period, students were led to sense the inner body to heighten the connection of their being in space and time, we uses the trained body text, and voice, to generate material for the performance. Many times the students would use the words like 'conversation, support, truthful, attention and attraction. ‘Macbeth was conceived out of a supernatural belief during the Shakespearean time, under the influence of King of Scotland, who believed in the spiritual realm. The conceiving of Macbeth juxtapose my research of dying art forms in Southeast Asia, which I encountered the dying of an art form when it loses its 'spirit' to connect and evolve, being framed in a form that would not allow the 'spirit' to transform.

When we preserving an art form, do we preserve the technique or its spirit? So this have kept me thinking about how can I preserve the technique and spirit of an art form? If an art form loses its 'spirit' would it sustain and evolve? The process of interpreting Macbeth in Nanyang Spirit continues to shape my search of spirituality in the arts, trying to capture a glimpse of what our Nanyang Artists, the forerunners spirit' was like, is like, and going to be like? I often question myself what teaching in the physical body means? What is the value of arts in my practice? Unless I have an idea of what it means to me, I can't give what I don't have, can I? I think teaching and creating is metaphorically the same, both are giving part of yourself to the receiver'. So what do I embodied that allow me to give? My skills? My values My spirits? All these overwhelming questions are somehow making sense in the practice of creating this piece of work.

Interpreting classic work of the West using the techniques and objects of this region enable the youth artists to synthesis and cultivate their inquiry of identity and heritage. I think the process of creating the piece would allow youth artists to critically question the practices in the contemporary theatre and extend their capacity to query for deeper meaning in the arts. Dance and Theatre are redefine in its respective forms and physical theatre is the intersection of dance and theatre, which is exciting to create as this could be a new practice for artists to experiment and find new techniques for the contemporary practices of Theatre and Dance. Historically and traditionally in Southeast Asia e.g. Khon in Thailand; Sbek Thom and Cambodian Ballet in Cambodia; Human Marionette in Myanmar, are 'dance-drama' where acting and dance are inseparable. To revisit this dance-drama techniques in this region is something I am trying to bridge the gap in the arts at the same time open up new opportunity for the younger generation of artists to explore and redefine the heritage of this region.

Synopsis

Macbeth, one of the greatest tragedies ever written in the world of William Shakespeare. The play was based on the true story of Mac Beth and Mac Findlaich, King of Scotland in the 11th century. It was influenced by coronation of King James I as a celebration of his kingship. I am looking at Macbeth as an artefact to trace the root of the original intentions, to find new intersections of Southeast Asian spirituality in performance; that lives in the uncanny world of evocative objects that rooted in the heritage of this region.

I like how Sherry Turkle raises the question "what makes an object evocative?” She researches into the world of objects in her book Evocative Objects - Things We Think With. It is very real that objects have the power within to evoke memories, emotions, and even reveal history and exchange realities. As objects conjure memories and emotions, classical play would embody the 'truth' of the past as it is revived by the body of the actors that would share the essence and soul of the origin.

Investigating into the spiritual dimension of a play' is my continuous research of the dying art forms in Southeast Asia; finding the connections in which 'life' could be revived through the skills of the performers. We are like the "dalang", breathing life into inanimate puppets and hoping to find an answer to restore the wonder of the play by establishing new connections to the encounters. In Southeast Asian heritages, many live performances were derived from the supernatural belief of animism. Many ancient objects were regarded as a form of mediation to restore peace of the cosmic laws. Similarly, there were many myths in the performance of Macbeth over the centuries that has been presented not merely to audiences around the world, but has also haunted the performers.

Similarly, there were many myths in the performance of Macbeth over the centuries that has been presented not merely to audiences around the world, but has also haunted the performers.

"Theatre people are a superstitious lot, and anything causing as much trouble as Macbeth has a bevy of lore about it. For example, unless in actual rehearsal for the play or for an actual production, nobody utters the title/name "Macbeth." The play itself is commonly referred to in theatre circles as The Scottish Play. Of course actors do accidentally say the title of the play at times, and there are numerous beliefs on how to ward off the bad luck once this happens. Most of the variations include leaving the theatre, spinning around three times, cursing, spitting over one's left shoulder, and the waiting to be invited back into the theatre building."(2009-2016 Historic Mysteries)

The story of Macbeth spread far and near, interpreted by many theatre makers over hundreds of years, shaping and moulding the enigmatic fate of Macbeth into the culture of the time.

As we dwell deeper into the bewitching voices of the witches that stirred the heart of Macbeth and started the spiralling vicious cycle of his house, it can be an allegory of our current situation, the juxtaposition of the combustion of voices entailed by colonisation, World War II, and globalisation in Singapore. Engaging with the objects of our ancestors to evoke the story of Macbeth in our contemporary world, we want to raise questions that arouse further examination of authenticity and heritage, creating work that is deeply personal for the performers to reflect as well as bringing wider experience of everyone's desire to find their identity in a globalised world. Our young actors are employing their theatre practices to explore and embrace the 'Nanyang' spirit in this physical theatre work. They aim to bring out the performance practices from the old and new, through interpreting the classic play of William Shakespeare brought forward to the modern globalised society.